WORD PROCESSOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

October 28, 2013

Bureaucracy's Playthings

Shannon Mattern

For more than half a century Jack Wilkinson's office supply store stood on the corner of Allegheny Street and Cherry Alley in my hometown of Bellefonte, Pennsylvania. When I was a little girl, we'd make frequent visits—not to stock up on supplies for my dad's hardware store or my mom's classroom and volunteer activities, but at my request. On birthdays and Christmas I'd go in with a list: invoices, restaurant order forms, cash box, label maker, rubber date stamp, accounting book. These were my toys.

The playroom in our basement housed many unlicensed businesses: a restaurant whose menu blended some of my favorites from the Amity House diner (home of the fish-bowl sundae) and McDonald's; a bank with a drive-through window for bikes; a Matchbox car dealership; a hospital for my Glamour Gals and my brother's G.I. Joes; and, because this was the era of Miami Vice, a drug-trafficking "shoppe" where we sold generous dime-bags of all-purpose flour. The neighborhood kids were both our staff and patrons. Everybody—even those to whom we sold controlled substances—got a receipt, made out in duplicate. Everybody received exact, if fake, change. Everybody had a color-coded customer or employee file, with a nametag crafted on my hand-held Dymo label maker (which had its own label).

We were weird—delightfully so, I must say. And we were into the "aesthetics of administration" well before art historian Benjamin Buchloh coined the term in the early '90s. Which explains why the burnt-orange copy of Mina Johnson and Norman Kallaus's 1967 Records Management textbook sang to me from the shelves of the Reanimation Library during a recent visit. From Johnson and Kallaus we learn immediately that the stuff of my childhood play is actually quite serious business:

In the average business office, record making constitutes approximately ninety percent of the activity. Alert businessmen keep a constant check on their costs of doing business. One paper lost, mislaid, or delayed can and often does inconvenience and retard a dozen or more people in their work (1).

Furthermore, "few people realize that, of all the service activities of an organization, the creation and the storage of business records are the greatest consumers of space, salaries, and equipment"—in 1967, at least.

One thing that records management will likely not consume, however, is your rapt, undivided attention. I had to take the book up on my roof, and walk laps while reading, just to keep myself awake—particularly while slogging through chapters on the rules of alphabetization (e.g., how to handle hyphenated business names? wouldn't you like to know!) and on the differences among "terminal digit," Browne-Morse Service Index, and Soundex filing systems. This certainly wasn't as fun as rubber-stamping phony restaurant receipts, affixing glittered stickers to indicate that they'd been "processed," and filing them away in hot-pink folders.

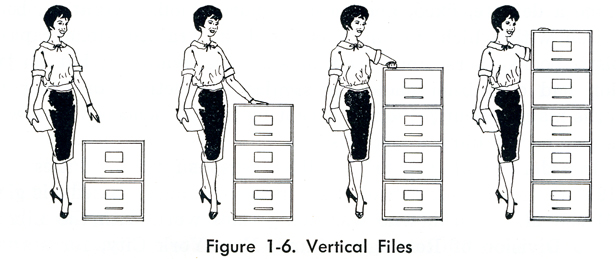

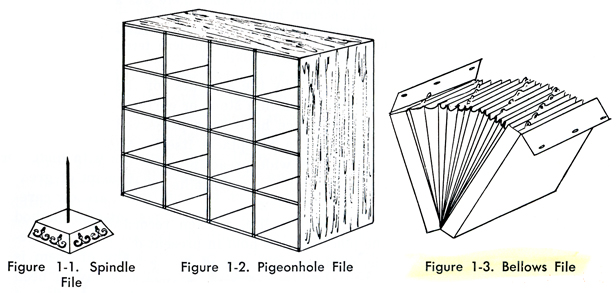

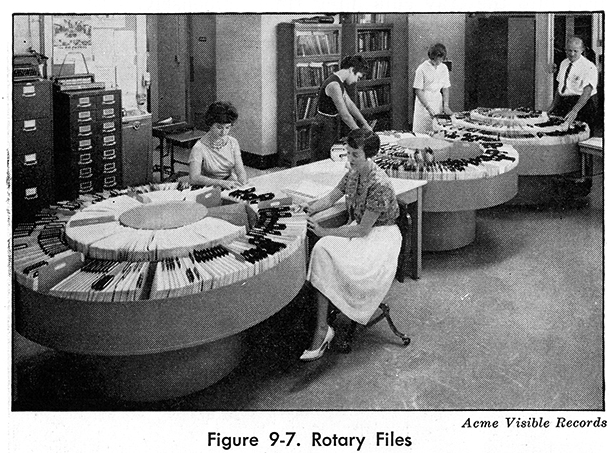

Then it struck me: the flair of filing was still here in Records Management—but it was in the implied aesthetic nature of the filing enterprise: in the alignment of tabs and arrangement of drawers. That pizzazz was to be found, too, in the style of the book itself—in its liberal use of diagrams and illustrations and photographs of state-of-the-art office equipment and fashionably dressed, well-coiffed office ladies. I figured, why not read Records Management against the grain, focusing less on the staid instruction and more on the aesthetic and even ludic nature of filing work? Why not read this textbook as a toy catalogue, or as a set of rules for a Monopoly-esque administrative game?

Toys For Serious Business

Filing tools—the spindle file, the pigeonhole file, the bellows file, the flat file, the Shannon file, the vertical file—have been around for centuries. But the First World War gave rise to a new era of business that generated an explosion of paperwork, and that paperwork needed to be filed away. "With the growth of businesses, the departmentalizing of activities, and the necessity of depending upon the written word rather than upon memory," Johnson and Kallaus write, "[t]he person who is responsible for the orderly arrangement of those papers has one of the most responsible positions in any business office" (2). Those individuals who held the new and noble position of "Records Manager" had to know "where each piece of paper originates and why, how many copies of it are necessary, how these flow through the different offices and departments, where they are stored temporarily and how, and what their end may be," whether immediate destruction, destruction after being archived, or temporary or long-term retention (9). How was anyone to keep tabs on individual forms as they floated through massive institutions? How could one find order in such seeming chaos?

Johnson and Kallaus explain how a file is processed: it's first inspected and "released" for filing; then it's indexed to determine where it should be filed; then it's coded or marked to indicate its placement within the file; then it's cross-referenced in case that file might be sought within the system under multiple names; and finally, it's filed away (89-100). Yet how feasible is it to expect our Records Manager to oversee every invoice, contract, and letter as it passes through five stages from its creation to its ultimate placement within a cabinet drawer? Media and legal scholar Cornelia Vismann, in Files: Law and Media Technology, explains that institutions can develop ordering systems that precede the existence of the material files themselves. These procedures for "uniform and precise handling," documentation and archiving can "ensure that files already assume an orderly shape when they are being compiled," rather than requiring that they be tidied up afterward (100).

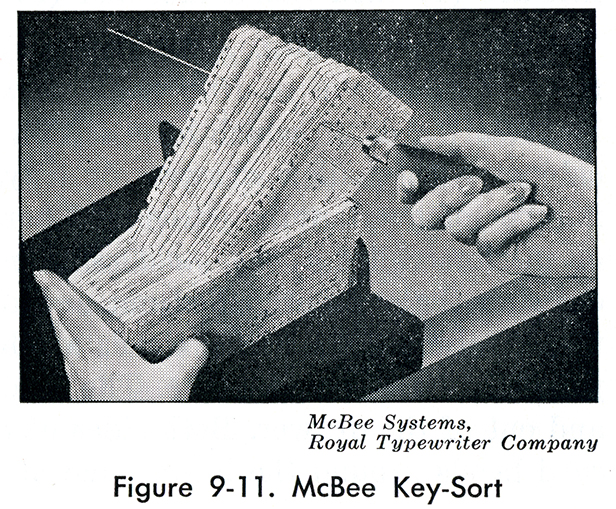

The files themselves display directions for their own movement through this chain of operations. "Address, location, and hold-file notes belong to the arsenal of operators that process the automobility of files," Vismann writes, and that allow those files to "move themselves from department to department" (138). Sometimes even the form of the record embodies cues for its handling. Consider the McBee Key-Sort, which is used to organize filing cards. The edges of the cards have holes, some of which are notched. When a long needle is inserted through one of those holes and lifted up, only the non-notched cards rise, thus filtering out the irrelevant records.

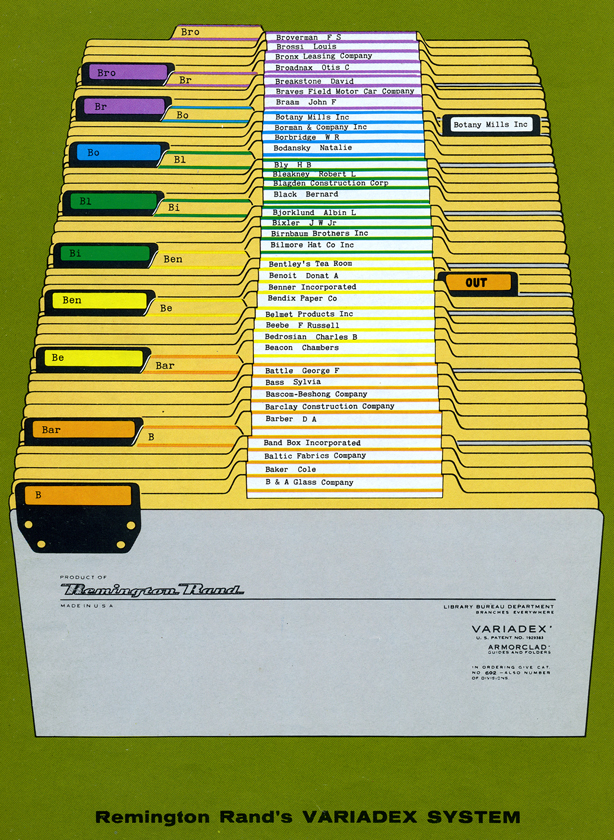

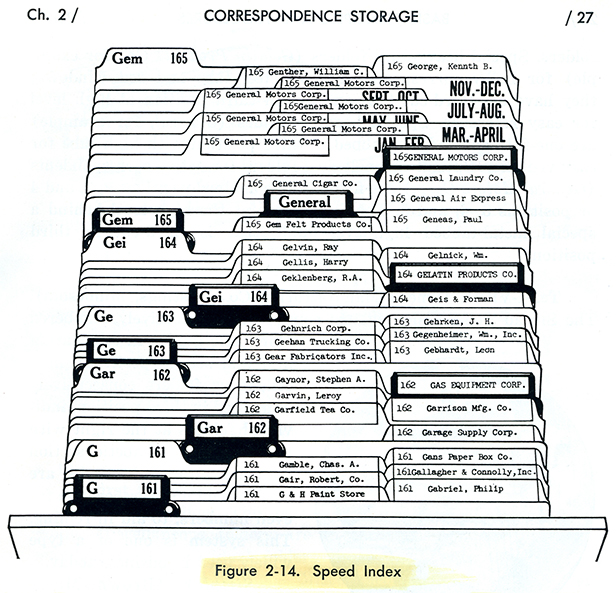

Once we get to the actual placement of records within the files, we can turn to other gadgets and techniques for directions on how to proceed. The architectonics and aesthetics of the filing mechanism can embody its filing logic or ontology—that is, its structural framework for organizing information. Consider Remington Rand's Variadex system, with its color-coding and tab-positioning: "[a]lphabetic guides are in first position, miscellaneous folders are in second position, individual folders are in third and fourth combined positions, and special guides for names having a large volume of correspondence or for names of frequent reference are in fifth position" (22). Or take the Oxford Filing Supply Company's Speed Index, which adds tab height, width, and materiality into the filing ontology:

The main alphabetic guides are numbered consecutively, are made with one-fifth-cut tabs, and are staggered in first and second positions. Their steel tabs and heavy construction afford prolonged life and usage. Individual name folders, with one-third-cut tabs are staggered in two positions, second and third. The folders tabs are at a lower level than the guides, to protect them from becoming 'dog eared.'.. Salmon-colored one-fifth-cut miscellaneous folders have tabs in the first position, at the lower level of the other folders. Special heavy-duty folders... for bulky correspondence have steel tabs and red windows; they have one-third-cut tabs and are in third position at high level for easy reference... (27-8)

It's as if we've taken an alphanumeric outline we might sketch out on paper, and dimensionalized and materialized—and even decorated—it.

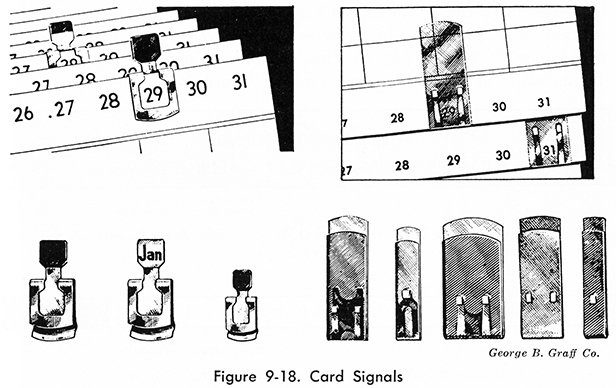

We have other aesthetic cues, or "signals," at our disposal, too; Johnson and Kallaus suggest that we use colored card stock, special printed edges, and removable metal or plastic tabs in a variety of colors and shapes—or what I like to call "file bling"—to make sure records are filed appropriately, and to aid in retrieval. We can perforate our file edges to allow various colors to show through, or we can clip the corners of our files to code them. Even our filing furniture—our chests and bureaus and cabinets, some of which can spin around or release fold-out appendages—aids in directing files through the system: files are "ordered in a way," Vismann writes, "that furniture turn[s] into addresses, that is, into pointers for the retrieval of records that [are] counted by chests" (98).[1] In other words, our filing containers help us gauge the size of our collections, and aid us in navigating through them.

Particularly when records managers adopt filing systems based on reference numbers—alphanumeric sequences that indicate what's in each file, where it's located, when it was created, and which office is responsible for it—that number essentially embodies "the administrative macro-order." The reference number references not only a file's placement within a drawer, Vismann says, but also,

the topography of the shelves as well as the spatial arrangement of offices—until the entire administration is nothing but one big filing plan. Micro- and macro-order are interlocked in such a way that the individual file represents the entire universe of an office, while a twentieth-century office building, in turn, turns into one "enormous file" (145).[2]

There's a playful dollhouse / house of mirrors / Alice in Wonderland quality to this telescoping of scales: the file and the institution are micro and macro models of one another.

Johnson and Kallaus address the advantages and disadvantages of various systems—some systems are better or worse suited for firms whose geographic reach is expansive or limited, or who are involved in few or many lines of business, for example—but it's important to note that, sometimes, choosing a filing plan is simply a matter of cultural, or even aesthetic, preference. At the turn of the 20th century, for instance, Europeans and Americans clashed over their taste in binders. While all binders serve to "mechanize" a particular mode of organization—"Starting with the punch," Vismann writes, the record's "individual physical parts predetermine a clear order: punch, open, fix, insert, close"—and necessitate an alphanumeric arrangement of their contents, there are variations in how that mechanization takes form (137). "Europeans cannot understand why the unnatural two-hand-pushing-on-the tongues movement would be preferred to the simple natural pulling motion needed to open two rings. Americans insist on the tongue and three rings" (quoted in Vismann 136).

And sometimes it's metaphysical. As the Leitz company acknowledged in a 1900 leaflet promoting its own biblorhaptes files, "The mechanism is the soul of the binder" (quoted in Vismann 133). At the same time, the spirit of the larger system—the file-keeping administration—is embodied in that tiny mechanism: in those rings and notches and tabs. The individual files, and even the individual components of each file, represent the "entire universe" of a bureaucracy. "Files are the mirror stage of any administration," Vismann argues (92). "The entire order could be derived from the smallest element, that is, the state from a single file" (133).

Bureaucratic Puzzle Pieces

Perhaps this is our game: to puzzle out the institutional order from its filed-away parts—or to move in the opposite direction, from the macro to the micro. By studying the files of a governmental archive, for instance, as anthropologist Ann Stoler has done with Dutch colonial archives, we might be able to discern the state's means of defining and disciplining its subjects, or of justifying its own existence through the exercise of power. Yet by also acknowledging the aesthetic and ludic natures of filing, we might also come to appreciate the system's fissures—the spaces where play and resistance might take place. The very fact that files essentially direct their own processing, Vismann suggests, means that "those who work with [them] can easily be granted autonomy in their small world of files" (137). What to do with this autonomy? Dadaist painter and poet Kurt Schwittzers, who worked for a German manufacturer of writing utensils, took inspiration from "abbreviated printed labels"—e.g., the "Roser-Rud; Schall; Scham-Schaz" tabs on individual folders—in creating his "Ur Sonata" sound poem (Vismann 185, note 60). And many conceptual artists embodied critiques of the bureaucratic system in their own explorations of the "aesthetics of administration."

What's more, the sheer scale and anonymity and lack of individual accountability embodied in bureaucracies offer opportunity for opposition. Ben Kafka, in his history of paperwork, suggests that late-18th-century French bureaucrat Augustin Lejeune might have sought to "slow down the pace of [the state's] political violence by burying it under paperwork"—drowning the Committee of Public Safety in excessively detailed reports—and by then burying that paperwork itself. Lejune recognized, Kafka writes, that

the proliferation of documents and details presented opportunities for resistance, as well as for compliance... The materiality of paperwork in fact presented unmistakable opportunities for resistance to the terrorist regime through everyday strategies of deferral and displacement (67, 74).

There's thus generative potential in losing and delaying files. And even the planned disposal of files offers opportunities for creative destruction. Johnson and Kallaus suggest that files can meet their demise through crushing, macerating, burning, shredding, or, least interestingly, by selling them to paper-collection agencies. Such a range of performative possibilities.

In addition to these opportunities for bureaucratic resistance, I suggest another: pure play—with stamps, label-makers, and file folders in all crazy colors. Creative experimentation with these tools of administration can show us that the file need not function as the building block of bureaucracy alone, but can instead serve as a modular unit for an imaginative universe, an experimental ontology. Or even an illegitimate basement business where kids can offer imaginary mortgages and serve up pretend hamburgers to their neighborhood friends, worrying not about proper routing or cross-referencing, but instead about the pleasurable aesthetics of paperwork.

[1]In the mid 18th century Vincent Gournay ascribed so much agency to the bureau that he described the rise of a new form of government: "rule by a piece of furniture," or bureaucracy (quoted in Kafka 77).

[2]See also Alexandra Lange on links between the standardization of filing and the rise of the skyscraper—particularly the work of Le Corbusier, who described his designs as "generated from the inside out, dimensioned by the path of standardized white paper" (60).

Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, "Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions," October 55 (Winter 1990): 105-143.

Mina M. Johnson and Noram F. Kallaus, Records Management: A Collegiate Course in Filing Systems and Procedures (Cincinnati: South-Western Publishing Co., 1967).

Ben Kafka, The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork. (New York: Zone Books, 2012).

Alexandra Lange, "White Collar Corbusier: From the Casier to the cités d'affaires" Grey Room 9 (Autumn 2002): 58.79.

Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Cornelia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology. Translated by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008).

Shannon Mattern is an Associate Professor of Media Studies at The New School. She writes about libraries, archives, and other media spaces. You can find her at wordsinspace.net.

View Records Management in the catalog.