WORD PROCESSOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

October 15, 2012

Puppets Are Not People

Craig Epplin

Stretched out inside a puppet, the open hand will assume one of just a few different positions. The thumb makes for a natural arm, but the other four fingers can be extended, folded down, and held together in various combinations. The book Making Puppets Come Alive: A Method of Learning and Teaching Hand Puppetry (1973) lists six possible techniques, highlighting one, in which the fingers are arrayed in a 1 / 2 / 2 pattern, as the most comfortable. "In this position," write the authors, "your hand is more relaxed and the puppet's arms can spread the entire breadth of its body. There are also no left-over fingers to conceal in the puppet's costume." Every part of the hand plays a role; the puppet's body is made to coincide with the hand's natural reach.

This recommendation exemplifies the pragmatic nature of this book, which is intended as a novice's guide to the basic skills of hand puppetry. For the beginner, this genre is an obvious starting point. Hand puppets, we read, "are the most natural and direct to use," as they facilitate clear, straightforward expression. Through them, the "puppeteer can express himself directly [...] without having to overcome the complex problems of control by rods or strings." In its simplicity, in other words, hand puppetry is an art of transparency. Among verbal constructions, its most natural correlate is probably journal writing, which also aims at direct, unmediated access to our inner reaches. For the hand puppeteer, the layer of cloth that covers the hand is a thin, efficient conduit for human thought and feeling.

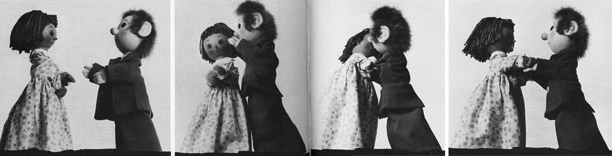

The notion that hand puppets are relatively uncomplicated channels for expression is on display visually in Making Puppets Come Alive. Included in the text are numerous photographs, which demonstrate the gestures and movements described by the authors. The stars of the show are a little woman and a little man. The two resemble each other. Their eyes are vacant, their mouths diminutive and unremarkable, their noses similarly generic. Their wardrobe is basic and understated: overalls, a suit, a long dress. Everything about them is more or less bland. They announce nothing so much as their condition as empty vessels for the supple fingers of the puppeteer. In the photos, the two puppets greet each other. One shares a secret with the other. They kiss and embrace. Actions and gestures, controlled by the human hand inside, take precedence over any inherent physical qualities found in the puppets themselves.

This apparent neutrality, however, is a mirage—as is always the case. Even the most anodyne designs glimmer in their flatness. Everything contains and reveals an aesthetic attitude; implicit in the most straightforward set of instructions is an argument about what makes up the world and how we should act within it. Think of an IKEA manual: Don't the blank outlines of the laboring human figures mirror the aesthetic of unadorned, modular surfaces in their catalogue? Something similar is at work in Making Puppets Come Alive, itself also a sort of instruction manual, with its blend of practical advice and implicit ontological claims. Among these claims, one strikes me as particularly important, and I'd like to explore its consequences in what follows. The claim can be distilled and stated plainly: Puppets are not people.

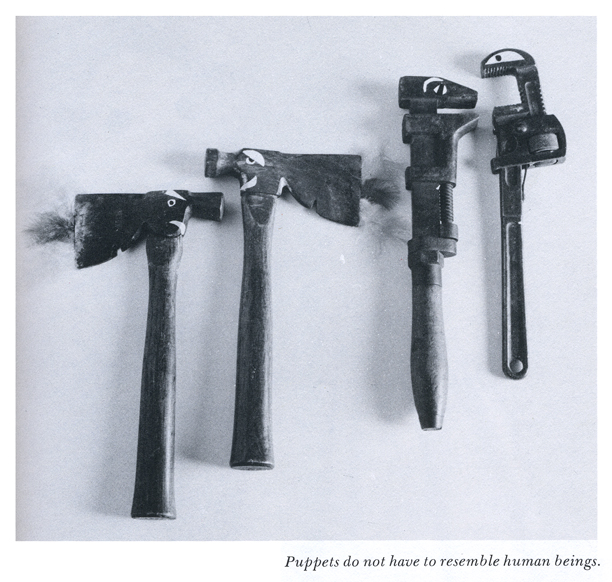

This point, which seems alternately self-evident and surprising, is reiterated on several occasions. "A puppet is not a little human being," we read in a section on the appropriate use of oversized props, just as, in a discussion of how to enter the stage, the authors remind us that "puppets are not people and do not have to follow the laws of human conduct." For this reason, walking through a door is perfectly permissible; so is popping straight up out of the floor. What holds for puppets' behavior is equally the case with their appearance. One of this book's most fascinating illustrations, a photograph of axes and wrenches decorated with eyes, bears a concise caption: "Puppets do not have to resemble human beings." The corresponding passage in the main text expands on this point: "An old dust-cloth, a feather boa, or a pair of bare hands operated by a skilled puppeteer can be just as alive and real to an audience as any human actor." Puppets are not people and need not even resemble them, in other words, but with proper technique they can prove to be adequate stand-ins.

The puppet is thus somehow both more and less than a human actor. It is endowed with its own unique capabilities, yet often aspires to be a real boy. These terms of comparison are common ones in the history of reflections on puppets. To name one well known case, in his 1810 essay about marionettes, Heinrich von Kleist lauded the nearly weightless grace of the puppet, which he contrasted with the inert heaviness of the human dancer. Puppets, for Kleist, are superior in this way to humans. The authors of Making Puppets Come Alive are similarly insistent on the uniqueness of puppets, their nonhuman nature, though they are less celebratory of this character than Kleist. For them, rather, the particular qualities of puppets should be understood primarily in the service of the mastery of an art. And thus the book's first chapter defines puppetry in terms of a clear hierarchy: "Puppetry is a performing art," we read. "The puppeteer is the artist, and the puppet is the instrument through which he creates living theatre." In other words, the material uniqueness of the puppet is valuable only in as much as it can be harnessed and set in motion by the sovereign puppeteer. Humans and the instruments they manipulate are to be strictly differentiated, and strictly ordered as well.

This dualism is, of course, not exclusive to the authors of Making Puppets Come Alive. For example, in his recently published Puppet: An Essay on Uncanny Life (2012), a lyrically haunting exploration of the world of puppets, Kenneth Gross at times seems to put forth a similar sort of two-tiered system. He likens the puppeteer's hand to a soul, rendering human agency the motivating force behind the puppet. He notes, in this direction, that all puppeteers are likely to manipulate many different puppets over the course of a career, that puppetry is a peripatetic art, that it demands promiscuous hands. The movement of these itinerant hands, Gross writes, makes up "the closest thing we have in the ordinary human world to the transmigration of the soul from one body to another, or from one creature to another." This remarkable comparison makes sense only if we consider that the puppeteer's hand comprises the life of the puppet. From this vantage point, the hand's particular properties, its rigidity or flexibility for example, are what give the puppet its unique character. We are back where we began, with the human hand in control of the puppet, itself reduced to a simple projection of impulses communicated by human prehensility.

Gross's story, however, is ultimately not so neat and clean. Already in his book's opening pages, he had also invoked the puppeteer's hand, here in relation to "the madness of puppets." This madness, we read, "lies in the hidden movements of the hand, the curious impulse and skill by which a person's hand can make itself into the animating impulse, the intelligence or soul, of an inanimate object." This madness further portends the partial separation of the hand from the rest of the puppeteer's body, an effect of "that more basic wonder by which we can let this one part of our body become a separate, articulate whole, capable of surprising its owner with its movements, the stories it tells." The hand, in this picture, is still the soul of the puppet, but it is a deranged one, driven ceaselessly outward, seeming to float in the air like an enchanted balloon. One might imagine that this madness is not entirely native to the hand itself, that it derives somehow from its momentary coupling to the odd form of liminal nonlife represented by the puppet. This is indeed the case: "The madness will also have something to do with the made puppet itself, so often a crude and disproportioned thing, with its staring eye and leering teeth, its tiny hands, the impossible red or blue of its face, barely human in form, like a monster or mistake, a fetus or a corpse." The hand controls the puppet, but Gross also allows that the puppet might uncannily transform the hand as well.

Similar complications are largely absent from Making Puppets Come Alive. In this text, puppets and humans occupy comfortably discrete realms, which don't generally bleed into one another. The life of the puppet becomes manifest only on specific occasions, during show time or practice, and it owes solely to the conjuring force of the puppeteer, who becomes a sort of shaman, capable of rousing and breathing life into inanimate objects. The shaman's trick, anthropologist Michael Taussig has written, "lies midway between sleight of hand and art," and the puppeteer too traffics in illusions. Illusion, however, is the not the same thing as mimesis. "The puppeteer," we read, "should use a puppet to create the illusion of life rather than an imitation of life." Effective animation happens not by virtue of strict similitude, but through the construction of an autonomous world on stage.

In this world, motion and gesture count for everything. This is perhaps the most important takeaway from Making Puppets Come Alive. One of the characteristic challenges of hand puppetry, we learn, is that the hand itself must channel the movements of an entire body. But what are the movements typical of the human body? The authors breaks them down into sections. Sometimes our heads convey a silent yes or no, for example. Or we point to ourselves. Other times we clap and wave. We rub our hands together. We tap and think and creep. In the world of people, all these things tend to occupy different conceptual spaces. The difference between an interior act like thinking and a social one like assenting is categorical in the world of humans. Among puppets, on the contrary, both occupy the same plane. Puppets think by carrying out the gesture of thinking, which is not so different from the gesture of walking or pointing or bowing.

Put differently, things happen more simply in this world. Or at least they happen in a manner that is more purely exterior. Everything here is the effect of some gesture. One section toward the middle of the book lists a series of pantomime exercises that eventually develop into little plots. They are meant as aids to help develop proficiency in handling puppets, and they tell us a great deal about the way that the world of puppets is a world of gestures. Here is one representative narrative:

Two puppets run onto the stage, from opposite sides, at the same time. They bump into each other in the middle of the stage. The first puppet motions the second to go away. The second puppet refuses and asks the first to leave. This continues until they have a fight and knock each other out.

What motivates this fight? Why are the two puppets enemies? What drives them to seek, in each other, their own bodily expenditure? We don't know, and judging by the omission of such details these are not fundamental questions to ask. Of course, this does not mean that it is impossible to convey the interior life or background of a puppet. Plot, voice, and skillful manipulation of the puppet's body all serve to endow these cloth creatures with motivations and emotions. In this way the puppet theater is not so different from other sorts of theater or even other narrative genres. What is remarkable to me, however, about these pages full of exercises is how these forms of interiority do not seem primary to the art of puppetry. What matters most, in the sphere of puppets, is the act of rubbing one's hands together, not the anxiety that underlies this fidgeting. What matters most is the headlong charge of one figure into another, not the anger that motivates this attack.

All of this makes perfect sense. Of course the fundamentals of puppetry reside in a series of physical movements that, once sequenced together, can then evoke in viewers the complex landscape of interior life. On the basis of these movements, lumps of inanimate material come to life, registering a wealth of emotion and density. This is the process of imbuing the puppet with a sort of humanity. Such would be, according to the authors, the task of the puppeteer. To return to a passage quoted above, in the right hands, a puppet "can be just as alive and real to an audience as any human actor."

However, in reading through Making Puppets Come Alive, I couldn't help but wonder about the reverse process: the imbuing of humans with the nature of puppets. What would it mean to think and move and be like a puppet? This question likely arose in response to the book's illustrations, photographs that catch puppets in poses that often seem to convey a sort of mute, very puppet-like and yet very human, embarrassment. Those photos reminded me that our emotions always involve a sort of theater—which is not to say that they aren't genuinely felt, only that their expression is so often a gestural affair. I began to imagine an alternate book with opposite aims: not to make puppets come alive, but to understand humans in terms of puppetry. Its title would represent a challenge, for the idea is obviously not to imagine puppets manipulating live humans. Rather, the concept is less fantastic: simply to learn from the world of puppets, to conceive of ourselves less in terms of motivations and thought and more in terms of physical gestures and bodily displacements. If puppets are indeed not people, what can we learn about ourselves from the world they inhabit?

We might think, in this direction, about the ways in which we are driven by forces that seem to inhabit us—not a literal hand, but something like it. This is actually a very old notion, as this "hand" has often been known as the soul, a word whose Latin forebear, anima, is still preserved in the term animate. And indeed, to make puppets come alive is to animate them, just as the process of setting clay or ink or digital dolls in motion is called animation, just as the project of the Reanimation Library is to breathe new life into old books. To make humans come alive, in this scheme of things, is also to animate them, to give them a soul.

Puppets teach us, however, that we don't necessarily require such metaphysical vocabulary to understand ourselves in this way. The animating forces inside us need not be understood as an immaterial soul. We might think, rather, of the coursing of blood that makes us swell up in rage or in arousal. Or also of the electrical impulses that neuroscientists study when they want to understand what part of the brain is activated by certain stimuli. In both cases, something moves us, something that we cannot control, something that is so deeply a part of us that the notion of control is rendered inoperative. This notion cuts against the grain of autonomous thought and reason as the engines of human behavior. It evokes, instead, something like the hand that Gross describes: a vehicle of madness, the madness that motivates the fundamental human drives of rage and love and play.

But to think of humans in terms of puppets is perhaps less about how we conceive our interior life than it is about how we inhabit space. This is a crucial question for the present and future of human coexistence, given the current, inexorable trend toward the privatization, policing, and evacuation of public areas. The past year has of course witnessed the blooming of movements whose crucial insight is that the stubborn act of visibly and joyfully occupying public space itself comprises a political act. One of the unique characteristics of the Occupy movement is how it has continually stymied attempts at its domestication by refusing to articulate demands. In other words, it has embraced a politics of the gesture, of bodily presence and weight, wherein the exterior action of inhabiting a park or a sidewalk becomes the basis of politics and the accepted political arena becomes a sham. This politics, like the world of puppets, is premised on exteriority. It is a politics that hinges on the ceaseless weaving together of movement and stasis.

We know very well what happens when puppets act like humans: We get theater, which ultimately forms the basis for a book like Making Puppets Come Alive. We know less, however, about the consequences of humans acting like puppets. The scenarios I've sketched here only scratch the surface. The puppetry of human experience exceeds the critique of detached rationality and goes beyond a gestural politics of occupation. This notion, rather, gets at a sensibility, simultaneously insistent and passive, that can be found in scattered realms of culture. To name just two fictional examples, I think first of Herman Melville's Bartleby, whose quiet refusal to leave defines his antagonism to work, and second of the work of Swedish artist Johannes Nyholm, whose memorable clay character Puppetboy darts around his small apartment, sweating blue beads and accomplishing nothing, as if constantly marking both territory and time. Something like automatons, something like the possessed, and also something like ordinary people, these figures exemplify a puppet sensibility: simultaneously agitated and weighty. Theirs is a world where will and inertia collide and annul each other, a world where stasis and movement collapse, a world in which puppets are indeed not people and in which people, in turn, are not fully people either.

Craig Epplin is an assistant professor of Spanish at Portland State University and an editor at Rattapallax magazine. He teaches and writes about the confluence of literature, media, and ecology in Latin America and beyond. He keeps a blog and occasionally tweets @craigepplin.

View Making Puppets Come Alive: A Method of Learning and Teaching Hand Puppetry in the catalog.