WORD PROCESSOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

March 10, 2014

Familiar with Apparition

Maia Murphy

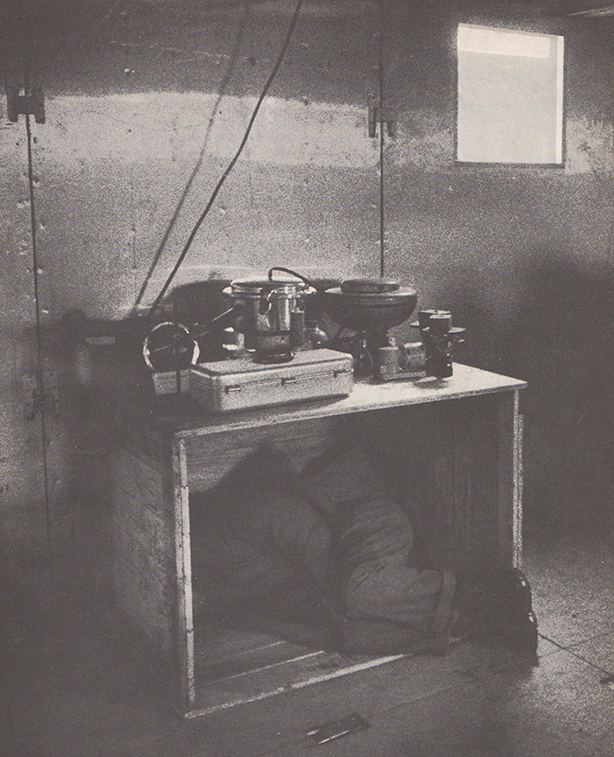

A scientist searching for sleep and privacy, taken from The Poles.

Rarely Left Alone

In the introduction to The Poles, Albert P. Crary lists the many problems of the polar scientist: the arduous life, the inefficiency of the work, the accumulation of data only by scattered fragments, and that he is "rarely is left alone" to experiment.[1] A penchant for solitariness can be a strong urge, presumably quenched by a life devoted to studying at the Arctic or Antarctic. Yet, Crary writes that even those who call the most far-flung places home may be left wanting for solitude.

Offering seclusion that is as alluring as it is terrifying, the cabin serves as home and muse to those interested in living apart from others. Turned outward, the cabin can be the first mark of an advancing civilization; turned inward, it offers mental retreat. Dylan Thomas, Thoreau, Virginia Woolf, Roald Dahl, Heidegger, and Carl Jung all lived or worked in a cabin, finding the structure supported the reflective habits required by the life of a writer. But, when solitude empties into confinement, one may become afflicted with cabin fever, as in the infamous case of The Shining's Jack Torrance. Taking polar exploration as a starting point, the following will discuss the attraction to, need for, and afterlife of the cabin.

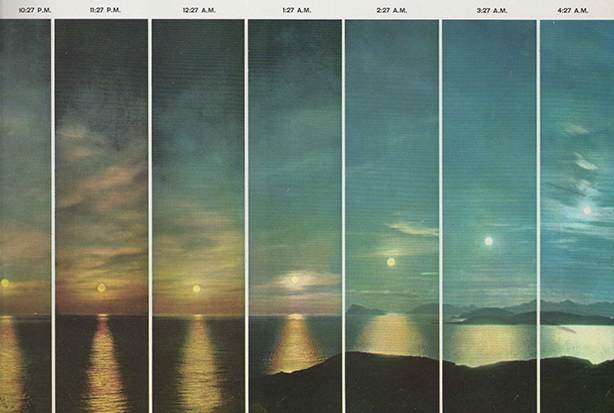

Days without end, taken from The Poles.

Semblance and Settler

The North and South Poles, which Charles Fort called a double "bloom that is stemmed with desolation," are characterized by incongruity in light and land.[2] Here, the sun will shine at midnight. At other times it won't breach the horizon for a month. Atmospheric layers of deeply contrasting heat and density can act as a lens that bends light rays. This can cause distant objects to appear close, or cause far away images to double. Ice crystals in the air reflecting light may render a low sun in triplicate (a sun dog) or halo a full moon with mocking copies (a moon dog). When winter's end approaches, and the sun is close to emerging after a month's long absence, a phenomenon called looming may cause the sun to appear as a mirage several days before it actually arises. The Poles are familiar with apparition.

The settler first came to know the Antarctic and the Arctic through semblance, the pursuit of each driven by conviction and braced by spectral sightings.

When Columbus looked at a map, he would see a basal landmass labeled Terra Australis Incognita, meaning unknown land to the south. Terra Australis Incognita was completely hypothetical, a continent only believed to exist. Theories about the presence of a far southern continent can be traced to at least the 2nd century AD, but were not confirmed until the first sighting of Antarctica in the 1820s. Before that, the land was a vision, made real enough by collective faith to be included on maps.

Commandeering a modest leather-clad boat, Ireland's St. Brendan the Navigator led one of the earliest explorations into the Arctic. In the early 6th century, he and his band of pilgrims searched the Atlantic for seven years for the Garden of Eden. The journey turned up no Garden, but the legend of St. Brendan's Saga, published some 300 years later, preserved the group's other discoveries. Among the sights they encountered were "mountains in the sea sprouting fire," which are thought to be volcanoes and cat-headed monsters with horned mouths, which are thought to be walruses. In the midst of the the Arctic Circle, St. Brendan's tribe caught sight of a "floating crystal palace."[3] This serene vision is thought to be the earliest description of an iceberg in literature.

The first record of an iceberg is a hallucination: the imagining of a grand home in the place of a chunk of ice that is as desolate as it is inhospitable. It is seeing nature, as many settlers came to, as both "poetry and property."[4] The fantasy of settling in the wild may end with a castle, but typically begins with something simpler, like a cabin.

A Cabin's Shape

A cabin is a simple shape. A triangular roof balanced on a square base, it is the first building a child can draw and mean home. When we close our eyes and conjure a cabin, we all imagine roughly the same shape. And we fill that space with roughly the same associations. Mark Wigley writes that a cabin is a "a retreat in time [to] a lost beginning. In the romanticized mythology of the immigrant pioneer, the domestication of the wild by the independent settler begins with the construction of a simple domestic space using primitive means."[5] A building made from natural materials like wood, and constructed with restrained, economic techniques, the cabin represents the ideal, vernacular architecture. Primitive and archetypal, it's the first structure an adult can build and mean home.

When wrested from a paper rendering to become a standing structure, the triangle balanced on a square base becomes a pediment resting on an entablature supported by a series of columns. The 18th century Jesuit priest and architectural theorist Marc-Antoine Laugier identifies these three elements as the fundamental blocks of architecture. Building on Vitruvius' primitive hut theory, in which all architectural forms derive from nature, Laugier theorized that the rustic cabin's elemental form and materials represent the only true architecture. In his Essay on Architecture, he continues that the primitive hut is both archetype for and wellspring from which all worthy structures stems.

Charles Eisen (1720-1778), Frontispiece of Marc-Antoine Laugier

Essai sur l'Architecture 2nd ed., 1755, engraving.

The French edition of Laugier's treatise included an allegorical frontispiece by Charles Eisen. Resting against the ruins of a classic structure, a goddess of architecture points to a primitive structure situated within a copse of trees. Branches naturally find one another, without need for bindings, to form the shape of the hut. This hut is autonomous, its appearance in the woods spontaneously produced. Emphasizing that architecture should exist within, and not at odds with, its setting, Laugier writes that, "man is willing to make himself an abode which covers but not buries him."[6]

Endure and Adrift

Ironically, one of history's most legendary cabins endures precisely because it was buried under ice for roughly 40 years. Known as Scott's Hut, the structure was used by Royal Navy Officer Robert Falcon Scott as his main winter base camp for a series of polar explorations between 1910 and 1913. Prefabricated in England and brought to Antarctica via ship, the cabin is located on the north shore of Cape Evans on Ross Island. It is 50x25 feet and was home to 25 men as they explored the region and sought out the South Pole.

Scott and a subset of his team reached the South Pole on January 17th, 1912, only to find they had been beaten there by Roald Amundsen's Norwegian Expedition in the race to the Pole. Recording the event later on, Scott wrote in his diary, "The worst has happened," "Now for the run home and a desperate struggle. I wonder if we can do it" and "Great God! This is an awful place."[7,8] The team faced exhaustion, starvation, and extreme cold with bravery, but Scott and his team succumbed to the elements on their march back from the pole at various points in March 1912. A few months later, some of their bodies were found in a makeshift camp, which was then transformed into a cairn and topped with a cross to serve as final resting grounds. According to glaciologist Charles R. Bentley, the cairn and bodies are likely now encased in 75 feet of snow and being carried toward the Ross Sea by glacial movement. Upon reaching its shores in approximately 275 years, the bodies may then drift into the ocean inside an iceberg.[9]

Scott's Hut was also buried by snow after it fell into disuse in 1917. It was not entered again until 1956 when it was unearthed by explorers, who vividly recorded their impressions of finding a space preserved at the moment of its abandonment. Still intact are the cabin's large dining table, bunk beds, laboratory, darkroom and galley. Packing crates, which doubled as makeshift interior walls, remain in secure stacks. Intensive cataloguing efforts revealed the cabin contains 8,000 preserved items including Heinz ketchup, ox tongue, biscuits, and tins of sardines. Because extreme temperatures depress the senses, Antarctica is typically devoid of strong smells. The cabin's interior, however, smells of pipe smoke, wood, leather, horses, and other scents emanating from a century ago.

Scott's cairn marked a structure that was lost to the elements, the final resting place of men who perished in nature. And so it is left to peacefully drift further out into these elements. In contrast, Scott's hut is now painstakingly shielded against the elements from which it was originally meant to protect its inhabitants. In the summer, when permafrost and ice melts, moisture seeps into the structure and begins to deteriorate the cabin and its contents. Human efforts to halt this deterioration are nearly as remarkable as the preservation caused by snow and ice. The UK Antarctic Heritage Trust has spent more than £10 million and unimaginable time to conserve Scott's Hut and three other Antarctic expedition bases. Their meticulous efforts parallel those of an art conservator, with one reportedly having spent two weeks "working to preserve the label on a bottle of Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce."[10] A fight against time and the elements is inevitably a lost battle, but the Trust is committed to securing the cabin in situ, identifying its remoteness as a quality as worth preserving as any of its contents.

Semblance and Sightseer

Similar to Scott's Hut, the cabin that once belonged to Henry David Thoreau is in the midst of an afterlife far more protracted than its life as a functional cabin. Synonymous with self-reliance, simplicity, and the belief that time spent in nature leads to spiritual awakening, Thoreau documented his experience of living in a cabin of his own making from 1845 to 1847. His cabin, famously located on property owned by Ralph Waldo Emerson at Walden Pond about a mile from Concord, Massachusetts, has long since "been adopted as an important reference point in American architectural culture, as a counterpart to the elitist and European Greek temple."[11] Picking up where Marc-Antoine Laugier left off, Thoreau found an appealing simplicity in espousing essentialist structures.

Despite Thoreau's meticulous documentation of constructing his home and its enduring status as an architectural landmark, the original cabin has long vanished. Nobody is sure what became of Thoreau's cabin after he left it. Resourceful locals likely moved the cabin several times, depositing it in various places around Concord like a shell being passed amongst hermit crabs. Perhaps, eventually, it was scrapped for parts and dispersed. For years, a visit to Thoreau's cabin meant a visit to a marker representing its original location and four posts roughly outlining its foundation, but no cabin itself.

Until 2010, when a class from the Georgia Institute of Technology built a replica of Thoreau's cabin as accurately as possible using descriptions he left behind and limiting themselves to the tools and techniques of his era. The new cabin is located near a parking lot and is marked by a statue of Thoreau with an outreached hand into which people place books, flowers, and in at least one case, an iPhone. Countless people make the pilgrimage to visit this spectral version of Thoreau's cabin. While Scott's cabin was dragged out from underneath the elements to be documented and preserved, Thoreau's cabin is a semblance of a structure that had long-since disappeared. This cabin wasn't simply rescued; it was resurrected.

Whether visiting Thoreau's cabin via the written word, traveling to the original site or its approximate reproduction, there is an appeal to entering a space designed to satisfy personal predilections and private use. Similarly, we are thrilled to gain entry to Topkapi Palace, the White House, and Versailles, all spaces intentionally built for highly exclusive access. At exclusivity's end is solitude. This thrill of intrusion intensifies and darkens when entering a structure built for one, as in the case of a profoundly reclusive cabin dweller.

Rarely Not Alone

From 1971 until his arrest in 1996, one of history's most infamous recluses, Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, lived without running water or electricity in a remote cabin of his own making near Lincoln, Montana. Avoiding first cities, then industrialized life, and finally other people, Kaczynski lived the life of a hermit, steadily filling his 10x12 foot cabin with depraved writings and objects. During this time, he completed his manifesto "Industrial Society and Its Future" and built and sent 16 bombs, resulting in the deaths of 3 people and injuring 23 more. In the twenty-five years he lived in the cabin, Kaczynski only invited two people inside.

Since its inhabitant left, the cabin has shuffled through several contexts as a stand-in for Kaczynski himself. Announcing the inadequacy of a conventionally scaled model and seeking to plead insanity for their client, Kaczynski's lawyers intended to submit the whole cabin as evidence to be presented to the courtroom. The lawyers argued that, "to be taken inside the brutally minimalist building was to be taken inside a deranged mind."[12] On Dec 2, 1997, the cabin was shipped from Montana to Sacramento, California, a 1,100-mile trip that took 3 days. In 2008, the cabin traveled again, this time to Washington DC, for installation in the Newseum where it remains on permanent display. Exhibition signage points out a meandering line on the cabin's wall; this is the outline of Kaczynski's body made from the deposition of soot from his wood-burning stove and oil from his body that built up around him as he slept. The cabin is otherwise empty of furniture and items. This line, an inscription of Kaczynski's body onto the architecture, is the only element indicating the life the structure once held. Arrested at the entrance of his cabin, which was immediately cordoned off by the FBI, Kaczynski and his home nevertheless remain inexorably twined together. Each, in turn, is used to invoke the presence of the other.

Do you have / are you?

- Always feeling tired

- Feeling unproductive and unmotivated

- Feeling sad or depressed

- Lethargy

- Difficulty concentrating

- Craving carbohydrates or sugar

- Difficulty waking in the morning

- Sleep disturbance

- Social withdrawal

- Restlessness

- Lack of patience

- Irritability

- Frequent napping

- Hopelessness

- Changes in weight

- Inability to cope with stress

- Distrust of anyone you are with

- Urge to go outside despite rain, snow, darkness, or hail

Cabin fever self diagnosis test

Cabin Fever

Kaczynski now lives at the Administrative Maximum Facility in Florence Colorado, where he is likely locked 23 hours a day in a cell approximately 33 square feet smaller than his cabin. When asked about his experience there, he replied, "I am afraid that as the years go by that I may forget, I may begin to lose my memories of the mountains and the woods and that's what really worries me, that I might lose those memories, and lose that sense of contact with wild nature in general."[13] Clearly, Kaczynski was a sociopath whose withdrawal from society into a cabin exacerbated, but did not cause, his paranoid and violent tendencies. Nevertheless, his fear of a loss of contact with nature is a signature symptom of the quasi-mythical illness cabin fever.

Cabin fever was first recorded in 1918 as the need to get out and about, and defined in The Poles as "the wild yearning for sun and space."[14] It can be experienced by one person or a small group, and is typically induced by spending extended time in isolation or confined space combined with aimless activity. At the poles, cabin fever can be aggravated by peculiar behaviors of light, particularly when they cause circadian rhythms to lose reign. One may suffer from The Big Eye, characterized by sitting sleeplessly until the morning. Another side effect is The Long Eye, which, according to one witness to a Long Eye-victim means, "They stare right at you, but never see you. They never say a word to anybody. They have a 12-foor stare in a 10-foot room."[15] The sufferer of the Long Eye may look out to a horizon waiting for the sun's return, perhaps even willing to settle for its familiar, looming hallucination

[1]Albert P. Crary. Introduction. The Poles. By Willy Ley. New York: Time-Life Books, 1962. 7.

[2]Charles Fort. "Lo!" The Complete Books of Charles Fort: The Book of the Damned / Lo! / Wild Talents / New Lands. New York: Dover Publications, 1975. 732.

[3]Robert Sullivan. "In Saint Brendan's Wake." Villanova University, Irish Studies Program. n.d. web.

[4]See Donald B. Kuspit. "19th-Century Landscape: Poetry and Property." Art in America 64, no. 1 (January / February 1976), 64-71. Though focused on 19th century American landscape painting, Kuspit's discussion of taming primordial experience speaks to broader themes within exploration and settling.

[5]Mark Wigley. "Cabin Fever." Perspecta Vol. 30, Settlement Patterns (1999): 123.

[6]Marc-Antoine Laugier. An Essay on Architecture. London: T. Osborne and Shipton. 1755. 10.

[7]Robert Falcon Scott quoted in Ley, 57.

[8]Robert Falcon Scott. Excerpt from The Last March by Robert Falcon Scott. Explorer Journal. American Museum of Natural History. n.d.

[9]"Scott of the Antarctic. Robert Falcon Scott and Expedition perish." Discovery UK. Discovery. 28 Mar. 2011.

[10]Ben Fogle. "The little huts where heroes were made." Daily Mail Online 9 April, 2011.

[11]Andrew Ballantyne. Architectural Theory: A Reader in Philosophy and Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2005. 30.

[12]Wigley, 124.

[13]Theresa Kintz. Interview with Ted Kaczynski. Green Anarchist. 1999. Republished by The Anarchist Library. Web.

[14]Ley, 163.

[15] Ibid, 176.

Maia Murphy is the Program Director for Recess Activities (NYC). Her work has been included in publications from The Paris College of Art, The Artist's Institute, Abrons Art Center, Bomb Magazine and The Hürriyet Daily News and she has shown work at the Invisible Dog Gallery (NYC), Arthur Rambo (Philadelphia) and Concrete Utopia (NYC).

View The Poles in the catalog.