WORD PROCESSOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

August 12, 2013

The Reanimation Library: Collection or Assemblage?

Will Saunders

"Life is a state of uncertainty and risk, of fragile adaptation to a past and present environment that the future cannot judge."[1]

Prologue

On arrival at Andrew Beccone's Reanimation Library in Brooklyn, New York, you intuitively fuse the multi-faceted display: Andrew is a trained librarian; he calls the project a library; it is one. However, his project has so many auto-ethnographic tendrils and odd juxtapositions that it seems apt to open some of its narrative clusters. Is Andrew hiding? Is his desk lamp an agent in an assemblage of concealment? Or perhaps Andrew is waiting? His books, as they do, are huddling on the shelves in order to keep each other closed.

To partake in the library's Word Processor series I visited the library to select a book from the collection, through which I intended to formulate a reflexive piece of writing.

Choosing a Book

I don't want to reduce one book to a dated esoteric curiosity, as there is a tale of selection and inclusion inscribed in every one. Each also contributes to an overall presence that is augmented by a visitor's engagement with its architect, Andrew. There is a feedback in which the collection provokes questioning that, in turn, goes some way to inform future additions.

I conversed with Andrew (within earshot of the books).

Will Saunders: There seems to be a theme of legitimate but almost maverick optimism about the world [in the collection].

Andrew Beccone: Absolutely, for me its the most uncanny characteristic ... the actual amount of optimism that it contains ... that optimism is based in this unbelievable faith in the power of technology taking us into this utopian promised land which we now know is not around the corner.

WS: How did this theme come about do you think?

AB: The bulk of this collection was probably from the 1940s to the 1970s and there's actually something really wonderful about printing technology during that period of time ... it got very experimental in some ways ... I guess layout was still a physical process.

I decided that a direction of investigation through my book would be to shed light on this veil of optimism and see if the image content had anything to say about it. Another could be what I have already called the library's auto-ethnographic tendrils. There is a travelogue aspect to this.

AB: I always look for books when I travel ... I have this fantasy of doing like a book mobile tour across the country. Basically like outfitting the van and y'know getting a bunch of scanners ... It's completely a way of me re-experiencing going on tour but hopefully I won't be sleeping on floors.

Dan Lichtman (a friend with whom I was staying in New York at the time of my visit to the library): As a visitor do I need to know about this travelogue side to the project?

AB: I don't think you need to know that to find it useful or interesting at all. But, there is absolutely a sort of like weird travelogue, travel diary component to this for me. I can look at things and I can remember where I was. This is the result now of basically compendium collecting. It's like a slow accumulation.

DL: Is there a system or set of parameters that guide what you collect?

AB: Since the library became publicly accessible in 2006 I've paid a lot more attention to what people are after and what people find interesting when they come in here ... there is an element for sure that is a response to the experience that I have with people in the space.. but yeah, largely it is still guided by my own idiosyncratic tastes ... there is a tension in that balance.

It was time to choose. Andrew provoked my selection process by showing me that he often groups certain books together through a similar fondness for them. By example he selected a few specimens and started drawing equivalences. I found myself imitating this performance, noticing that the collection's image-based consensus leads to uncanny links across subject matter. Against my initial intent I was pushed towards choosing two books.

They have differing agendas with regard to progress in the world (looking through the veil) and their image content is strangely similar (imaged based equivalences can be made).

Andrew

"There are heterotopias of indefinitely accumulating time, for example museums and libraries, museums and libraries have become heterotopias in which time never stops building up and topping its own summit, whereas in the seventeenth century, even at the end of the century, museums and libraries were the expression of an individual choice."[2]

Foucault's term heterotopia attempts to define particular publicly utilized sites as having spatial and temporal qualities that both contradict and have inextricable links with other sites. Heterotopias are outside of all other places, even though they can be located and visited. The Reanimation Library is a paradoxical heterotopia. It does accumulate and classify slices of time from elsewhere, but the process is curtailed. It's a collection of curios with a librarian capping its summit.

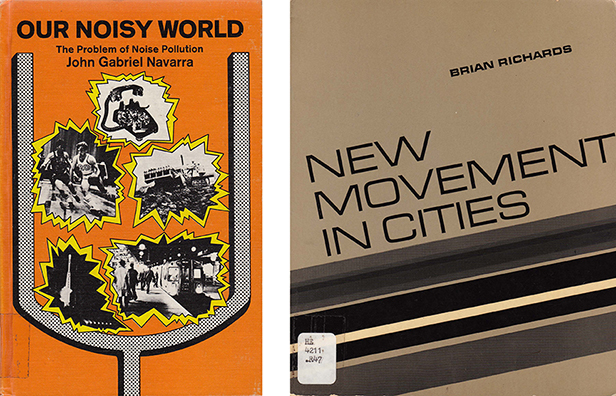

I emailed Andrew to ask him what journeys are behind Our Noisy World and New Movement In Cities. I would like to consider his answer through the following quote from Walter Benjamin's short essay "Unpacking My Library".

"I have made my most memorable purchases on trips, as a transient ... collectors are people with a tactical instinct; their experience teaches them that when they capture a strange city, the smallest antique shop can be a fortress, the most remote stationary store a key position. How many cities have revealed themselves to me in the marches I undertook in the pursuit of books!"[3]

AB: I bought New Movement in Cities from an amazing junk shop called The Thing in Greenpoint, Brooklyn in 2004. The place is really known for its basement full of LPs ... but it also has a pretty good book selection. I selected this book because I was attracted to its weird quasi-utopian view of public transportation and its bounty of amazing images. I'm definitely interested in urban planning/transportation, so this book was a no-brainer.

AB: Our Noisy World was purchased while I was gathering books for the Carlisle Borough Branch. I bought it at a used bookstore, which is something that I generally only do when I'm working on a branch library and have a limited amount of time to buy all of the books for it. Titles are usually the first thing that give me any idea of whether or not I pick up a book - though often the innards don't hold up (i.e. not illustrated, or the images aren't especially great). This, thankfully, was a case of title matching content—another no-brainer for me.

Andrew is not a collector of Benjamin's type; he doesn't engage with the institution of book collecting such as attending auctions and seems to have no completist intent. His hope is in his finds being reanimated through public library visitor use. It is important though not to overlook a sense of personal ownership here. This relates back to Benjamin who stipulated that regardless of his collective type becoming outmoded...

"the phenomenon of collecting loses its meaning as it loses its personal owner. Even though public collections may be less objectionable socially and more useful academically than private collections, the objects get their due only in the latter."[4]

The Books

Benjamin's sentiment of objects 'getting their due' could be subjugated by monetary value systems. Private art collectors for example will speak in a very similar way to belittle 'sluggish' state funded collections. I would rather approach the library as a shifting assemblage in which Andrew, his memories, shelved books, new acquisitions, visitors, and so on, produce a constantly shifting flow. In these terms, it is the books themselves that open up memories of book stores and racks of vinyl LPs. To extract a book is to also take Andrew's auto-ethnographic tendrils with it and break an interdependency with the library. I see the act of reanimating an image, text or whole book from this library as constituting action in Bruno Latour's terms.

"Action is not done under the full control of consciousness; action should rather be felt as a node, a knot, and a conglomerate of many surprising sets of agencies that have to be slowly disentangled."[5]

The Library

In fact, the whole library can be seen as a slow disentanglement of Andrew's previous actions. What lead him into this knot?

WS: The link between your DIY music activity and the library strikes me as interesting.

AB: Obviously, on the surface the library doesn't seem anything like an indie rock band ... it's not necessarily the content as much as the approach ... we booked our own tours, we recorded with friends, we put out our own records, we did all of those things because we wanted to do it. I feel like that has to be the case here ... I'm just going to build this museum ... so for the library it was just easy, having come from this background of going out on tour and putting out records and all that stuff, to realizing that there was not much of a gap between how those things happen ... I don't necessarily want to be driving around in a van playing for small audiences anymore, but I still feel and felt a very strong identification with that mode of operating in the world.

WS: It's expansive...

AB: Right, it's totally expansive.

The Library as Musical

Libraries cannot classify musical matter unless it is folded into a form of commodity. Musical matter at its point of production evades classification. It constitutes itself as slices of time but it can only be quantified by a library after abstraction to such things as paper scores or recordings. A poignant anecdote comes from an essay by Denis LaBorde, "Freedom for Music! Intuition and the Rule". He tells of how Stockhausen's text based composition Aus den sieben Tagen failed to be categorized as music in the National Library of France.

"Where to place Aus den sieben Tagen? Worried, the head of the music department wrote to the publisher Otto Harassowitz in Wiesbaden, who had published the work: 'p.s. Concerning Aus den sieben Tagen by Stockhausen, does this work comprise any music? Our edition consists only of literary texts.' The publisher asked the composer for information: 'There is no musical notation for this work, which must be interpreted only according to the explanations given by Mr. Stockhausen in the edition you have.' And that is why, in the file 'Stockhausen' at the National Library, Aus den Sieben Tagen is classified among the "literary texts" and not among the 'musical works'."[6]

So how does the reanimation library as an assemblage, house Andrew's node of musical action that lead to it? Here I would like to turn to to an idea posed by musicologist Ben Piekut who, I believe, takes a musical approach to scholarly enterprise. Rather than accept a canonical definition of John Cage he suggests thinking of him as a band member. He refers to a period when Cage took on bus tours with David Tudor and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company that were in practice more in tune with Henry Rollins (or Andrew Beccone in fact) than western art music.

"Considering Cage as band member allows us to recognize similarities in practice with other bands in the 1960s, but, more important, it also allows us to recognize how those messy overlaps have been cut or attenuated in favor of other network configurations."[7]

With 'messy overlaps' Piekut is referring to experimentalism on the ground in which small groupings of individuals distribute authorship and responsibility for creative output. By 'other network configurations' he is suggesting that a definition of Cage's experimentalism is not "magically coalesced around shared qualities of indeterminacy and rugged individualism." It is fabricated through the activities of "composers, critics, scholars, performers, audiences, students, and a host of other elements including texts, scores, articles, curricula, patronage systems, and discourses of race, gender, class and nation."[8]

Within this thinking, Andrew's library has a particular interest. It is inscribed with the ethos of shared authorship, garnered from years of action in a DIY indie band. Yet, on the other hand Andrew sits in the driving seat. As a recruit to the operation of reanimation I have become a floating member of Andrew's continuously regrouping band. The two books then are the instruments with which I will improvise.

Epilogue

New Movement In Cities, Brian Richards, 1966

The over arching intention of this book is to encourage an optimistic view of technologies that move people (rather than cars) through cities; technologies that Richards hoped would render the destructive accommodation of the motor car into city infrastructure unnecessary.

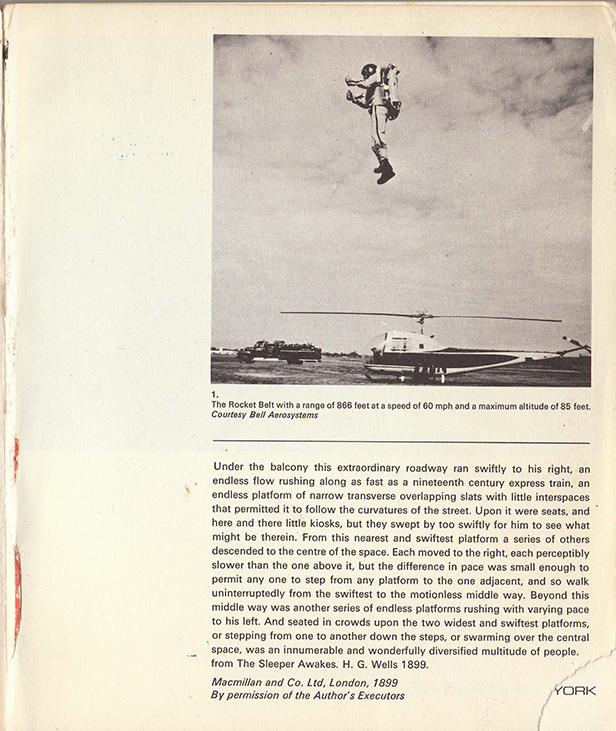

By way of a prologue to the book, Richards juxtaposes a photo of a man with a jet pack (that nostalgic image of human progress) with a quote from H.G Well's The Sleeper Awakes.

Seen through its visual material this book attests to the overarching optimism sensed in the library. However, Richards quote from science fiction is more enigmatic than this. In the sleeper awakes a man wakes up after 200 years to find himself at the centre of global wealth and surrounded by technological dystopia. Is Richards

1) Warning us to stay grounded; to stay out of science fiction and within concrete possibility?

2) Trying to entice a wider readership?

3) Joking?

Regardless, this initial unveiling of uncanny optimism has brought up a paradoxical layer.

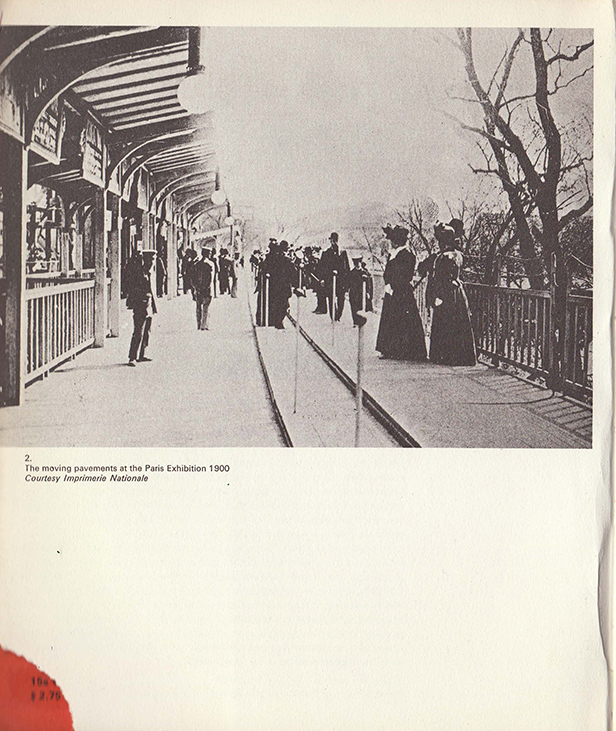

Over the page though, there is another image. HG Wells has been sandwiched. He is quoted describing an ominous labyrinth of moving walkways. The third image of this cute triptych shows the moving pavements at the Paris exhibition, 1900. Try for number 4...

4) Richards, as an architect, understood that the city and its vast network of bureaucracies, markets, conservationists, layers of politics etc.. has to be slowly tussled with in order to bring about change. Provocative images of optimism, borrowed from science fiction, can entice nostalgic ideas of progress but to avoid dystopian consequences one must introduce steady pragmatism. Richard's agenda then seems to be to reshape prototypes to fit into the very real mess of modern city infrastructure.

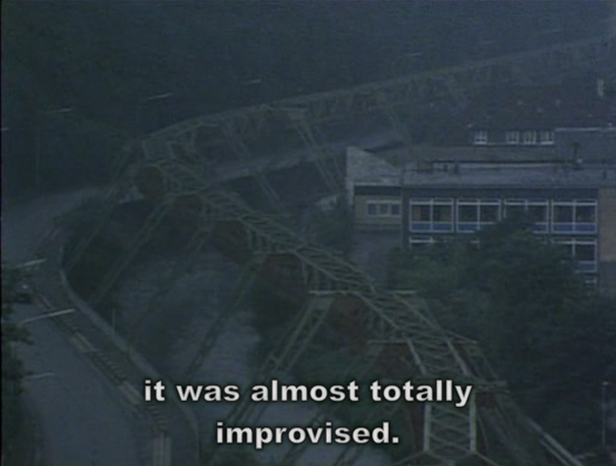

What Richard's book inadvertently shows is that this sort of technological injection was more likely to be actualized way before he wrote his book. For example, the suspended monorail still operating in Wuppertal, Germany that was first opened in 1901 is prevalent in his section on rail systems. In fact, Richards points out, any amount of improvement in rail systems would be in vain unless you can take control of passengers getting on and off the trains. "Systems are only as efficient as their weakest link."

In the documentary film Shoah from 1985 by Claude Lanzmann, a poignant moment hints at the sheer complexity of actualizing such a transportation system within city perimeters. The film shows an aerial view of Wuppertal's Schwebebahn, suspended over the river Wupper. Speaking over the top of the image as it follows the train is Anton Spiess, the german state prosecutor for the trial of Treblinka concentration camp saying "when the action itself first got underway it was almost totally improvised."

This improvisation is only present during a subjective period in a project's development. Once a technological project is turned into an operating entity the conflicting heads of its formation fade into the obscurity of subjectivity, whereas the thing itself forms an invisible objectivity. This is a point raised in Bruno Latour's scientifiction book about the death of Aramis, a 'failed' personal rapid transportation project for Paris.

"VAL, for the people of Lille, marks one extreme of reality: it has become invisible by virtue of its existence. Aramis, for Parisians, marks the other extreme: it has become invisible by virtue of its non-existence. The VAL project, full of sound and fury, arguments and battles, has become the VAL object, the institution, a means of transportation, so reliable, silent, and automatic that Lille residents are unaware of it. The Aramis project, full of sound and fury, arguments and battles, has remained a project."[9]

Cities now have become even more sprawling and unpredictable with an unprecedented number of people living in them. The technologies Richards talks about have dispersed into peripheral space such as airports, theme parks and large factories; points of least resistance. The vastly complicated city-destined project becomes diluted into a viable object.

There are of course examples of expansion that take prosthetic manifestations, isolated extensions or backups often in the name of the continuation of power during times of unrest. In Japan for example, the government are in the planning stages of building a backup city which will house the governing body in the event of an earthquake in Tokyo. There is also the infamous Mount Weather in the state of Virginia, an underground technologically progressive facility and the largest of many relocation sites where figures of governance are taken during disasters, civil unrest or attack.

Our Noisy World, John Gabriel Navarra, 1969

Published 3 years after New Movement In Cities, John Gabriel Navarra's offering has a more conservationist agenda but I would say they meet through an interest in movement. Our Noisy World is an educational resource for younger readers. It makes a case for care to be taken about unwanted sound, or noise. We need, he says, to understand that sound is an energy that needs to be controlled to avoid adverse health problems. He argues that sound pollution is reaching a point where its dangers and invasions are inescapable in the western world.

Navarra is however optimistic about how sound as a (considered and controlled) material can be utilized progressively within the remit of safety. For him "noise is a subjective phenomenon." This is interesting in relation to the idea of a projects bureaucratic, subjective and noisy disagreements being muted into the objective fusing of disparate elements into one transport network. Sound, more clearly than most material phenomena, continuously contradicts Latour's idea that something as complicated as a transport network becomes an object within the subjective notion 'on my way to so and so..'

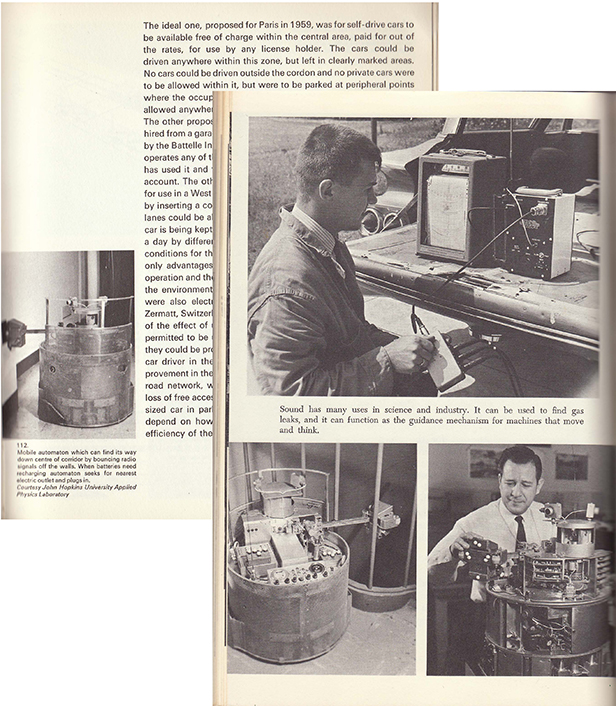

I would like to finish off this awkward clash of agendas with an enigmatic coincidence. Both of the books I took from the shelves of the Reanimation Library contain an image of the same robot. Neither book references it in their main body of text but its inclusion suggests sound as a material at the forefront of technology. Sound has a clearer role to play in the natural environment but humans have lost touch with it, defined it as a subjective, ethereal, evasive phenomenon. Perhaps this is because in the natural world the agency of matter of all kinds has a defined role. In our technologically advanced world humans condemn objects as inanimate and have forgotten the importance of the vitality of matter.

"There was never a time when human agency was anything other than an inter-folding network of humanity and non-humanity; today this mingling has become harder to ignore."[10]

[1]Latour, B. Aramis: Or the Love of Technology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

[2]Foucault, M. and J. Miskowiec. "Of Other Spaces". Diacritics, 1986. 16 (1): p. 22-7.

[3]Benjamin, W. Illuminations New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1969.

[4]———

[5]Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

[6]Latour, B. and P. Weibel. Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005.

[7]Piekut, B. Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-garde and its Limits. 2011, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011.

[8]———

[9]Latour, B. Aramis: Or the Love of Technology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

[10]Bennett, J. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2010.

Will Saunders is a musician based in London. His most recent collaborations have been with theatre makers Simon Vincenzi and Dickie Beau. He is researching a grouping of musical improvisors as part of a PhD at Westminster University. His website can be found here: www.juxt.co.uk.

View New Movement in Cities and Our Noisy World in the catalog.