WORD PROCESSOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

November 20, 2014

Without a Trace

Chloé Wilcox

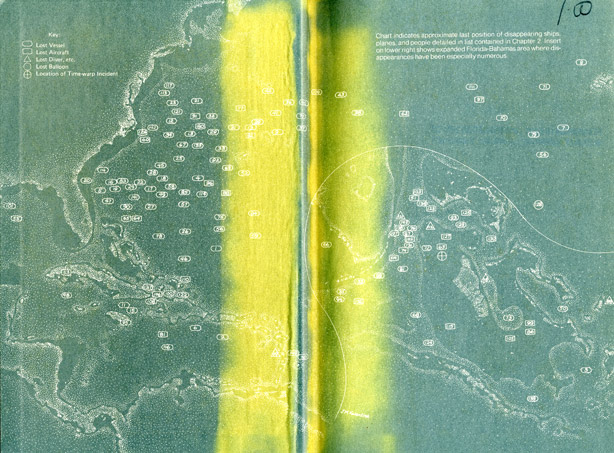

Things are happening in the Bermuda Triangle. There are sinkholes and stalker clouds; there are electromagnetic aberrations—faulty gyros, silent radios, wonky radars. There is time dilation; clocks stop. Messages get lost in the atmosphere to be picked up hours, months, years later by radio stations thousands of miles away. There are green lights, giant white bubbles, white fogs. Beneath the sea's surface, there is Atlantis ready to rise, Lazarus-like, from the deep. There's a plesiosaur too—Nessie flees frigid Scottish Loch for more temperate waters.

Without a Trace is Charles Berlitz's second book devoted to parsing these and other bizarre phenomena that transpire in the exciting patch of ocean girded by Florida, Bermuda, and the Sargasso Sea known as the Bermuda Triangle. Published in 1977, Without a Trace comes hot on the heels of Berlitz's first book on the subject, the aptly named 1974 bestseller The Bermuda Triangle. By Berlitz's account, this first foray into the mysteries of the "Triangle" really gets people going—letters pour in, hundreds of articles and books are published, his phone is ringing off the hook. So once it's translated into 20 some languages, he sees fit to add fuel to the fire and issues book no. 2 posthaste. Besides, six hundred "pleasure craft" go missing between 1974 and 1976 alone—and that's excluding military and trade vessels—so he's got ample material to work with.

+++

It all starts with Flight 19 out of Fort Lauderdale. It is December and it is 1945. The war is over. Five TBM Avenger Torpedo Bombers are due for a practice run. That morning in the rec room, Cpl. Allan Kosner has strange psychic feelings—starts to prickle, starts to see a purple glow—"For some reason I decided not to go on the flight that day." The flight commander, Lt. Charles Taylor, calls mom and says he's having a premonition too and would rather skip the trip. But that's no way for a commander to talk, and so he goes.

On the way home, machines malfunction and it's Taylor on the line, calling "Emergency!" Compasses are "going crazy." Soon he can only send messages; the receiver is out. "Don't come after me!" he says to Robert Cox, who's only trying to help over on starboard, or was it port? Down below in the control room, they're wondering what he's seen up there. "It looks like we're entering white water!" is the final call. Hours later, rescue mission Martin Mariner follows Flight 19 into the abyss.

But this isn't the first time something strange has happened up in those bright skies. Two years prior there is Robert Ulmer in his B-24 cruising a clear blue sky at 9,000 ft, the Bahamas splayed below. In an instant, the plane is out of control, "shaking as if it were being torn apart," and drops 4,000 ft. Ulmer and crew abandon ship, and the jet, relieved of its human haul, reverses course and travels 1500 miles across the Gulf of Mexico before crashing into a mountain. The "truly 'solo' flight," remarks wry Berlitz.

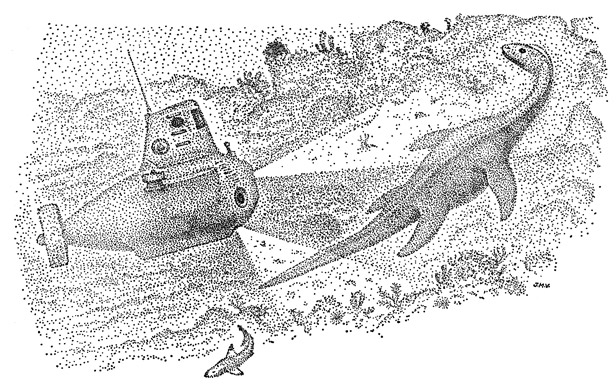

From 1945 on incidents accumulate, but nobody can make up their minds about what on earth (or off—and, by the way, Berlitz loves this kind of joke) is going on. As the book moves forward, it becomes difficult to keep track of what is happening to whom, and when, even where (if you thought always in the Bermuda Triangle, think again! There's Antarctica and Japan and South America too)—let alone why or how. And it's not just disappearances. There are close encounters with antediluvian creatures and malevolent ocean forces: Captain McCamis who sees a snakelike head, a "big lizard with flippers," and, when shown a drawing of a plesiosaur, says "Exactly!" Or, Ben Huggard, who swims across the sea in a shark safe tank, but is beckoned by a psychic power to quit the cage for a hammerhead's hungry maw.

"Dr. Manson Valentine, who is especially qualified for identifying and sketching animals by virtue of a doctorate in zoology and the fact that he is an artist, drew a picture of a plesiosaurus and, showing it to Captain McCamis, asked him if the animal he had seen looked like the picture."

Ben Huggard on his swim in a shark cage.

But really there is the problem of time:

There is Bruce Gernon Jr. of Boynton Beach, FL flying a Beechcraft Bonanza over the Bahamas en route to Bimini. Dad co-pilots. It is December again, now 1970, exactly 25 years (minus a day, plus 45 min) since the disappearance of Flight 19. Coincidence? Berlitz thinks not. [Coincidence of conglomerated B alliteration passes unmentioned.] Gernons Jr. + Sr. are stuck in an inimical doughnut cloud where everything is bathed in greenish light and islands pass beneath at top speed. All machines are out. The clouds rotate around the plane like a school of sharks. Father and son make a mad dash out of this celestial hellhole, and as their wingtips graze the cloudbanks, they're experiencing zero gravity! When they arrive in Miami moments later, they are miles off course and have arrived in half the time it should have taken. Time standing still.

Bruce Gernon with the Beechcraft Bonanza he was flying during the incident he experienced on December 4, 1970.

Cut to National Airlines turbojet flight to Miami. The plane goes off air control's radar for 10 minutes. Security is dispatched: foam truck, ambulance, police on the sweaty tarmac ready to bandage bloody, burnt bodies. "What the hell happened up there!" when it turns out no one has even swooned. Nothing, just a foggy flight. (But by now the wizened reader knows, never trust a fog!) Clocks are checked and tallied, and lo, the collective timepiece is 10 minutes slow. (Look! Grandma is minus one wrinkle, and, by the way, do I seem 10 minutes too young to you too?) "The unanimity of the watches suggests the possibility that for a certain suspended period the plane and its passengers were [sic] somewhere else—in another part of time."

Time folds, time bends, time takes you elsewhere, so that the land you see where there isn't any, and that floating "Flying Dutchman" over on the horizon between Eleuthera and Great Abaco are not figments but fragments from yesteryear. For once the sea was 1,000 ft. lower and the green islands wider. Once, the waters teamed with galleons and great beasts. Berlitz says these spooky sights are projections from the past, conjured up out of a soup of cosmic short circuits. And anyways, this doesn't just happen in the Bermuda Triangle, it happened in Antarctica too (and this is one of many Berlitzian tangential gems), when Admiral Richard E. Byrd flew the first flight over the Pole and, emerging from a fog, saw a land not blue and glacial, but hot and verdant, with long yellow grass, with men and mammals—great mammoths, huge buffaloes! "Look! Do you see it!" his brittle voice comes in through the static. "There is grass down there...the grass is lush...look how green it is...there are flowers all over...they are beautiful...and look at the animals..." Berlitz says Byrd's no hack nor kook; he peers through the fog and sees time play back, sees the icy continent as it once was in the verdurous bloom of its youth before it came to rest at the bottom of the globe. Like the Flying Dutchman and the untraceable landmasses, these grassy Polar plains are a physical memory caught in a crease of time. Pockets open in the space-time continuum and things slip in—and, if you're not careful, you might slip out, like poor old Carolyn Coscio who flew a Cessna 127 and was never seen again.

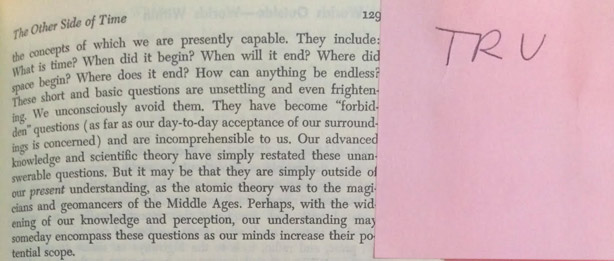

Berlitz reminds his perhaps now incredulous readers that there is still so much we do not know: "What is time? When did it begin? When will it end? Where did space begin? Where does it end? How can anything be endless?" He observes, "These short and basic questions are unsettling and even frightening. We unconsciously avoid them." The glitches, lapses, and repetitions are the machinations and malfunctions of a great system we as yet cannot comprehend.

Some statements with which I agreed.

Now Berlitz is really telling it to us straight: we might not know the answers to these vast and unsettling questions, but others elsewhere probably do. For it's not just glimpses of the past— accidental materialization of phantom yachts or sunken shores—that lurk in the Triangle's warm waters, there are also green lights and gold orbs. These are UFOs! And in them are the superior intelligent beings who may manipulate the space-time continuum at will.

A semi-official U.S. Coast Guard photo of UFO taken in 1952.

A fresh deluge of attendant incidents gushes forth; innumerable sightings around the world—many in the immediate vicinity of The Bermuda Triangle. Each of the inexplicable catastrophes enumerated thus far in Without a Trace is recast in a new (green, extraterrestrial) light. And the big reveal—what we (unknowingly) have been waiting for the whole book—the second half of Lt. Taylor's message that fateful December day in 1945: "Don't come after me—it looks like they're from outer space." There we have it: Those flashes of light, that fog, the greenish glow, the stopped clocks are simply symptoms of aliens entering the atmosphere! And isn't it interesting, Berlitz wants to know, that the first great surge of piepans came in 1947, only two short years after the five planes and their rescuers disappeared in a puff of smoke!

Now, the problem is why and how. Berlitz concedes, "A salient factor about UFOs is that concrete knowledge about them is totally lacking." And, indeed, this is an impediment to explaining the inexplicable activity in the Caribbean. Is the Bermuda Triangle a hotspot for spacenappings? Are Venusians establishing a new colony? Or are we simply dealing with carefree little green men curiously probing about, unaware of the havoc they wreak on the earth's magnetic field as they pop in and out willy-nilly.

In the end, it all boils down to a man named Charles Allen (alias Carlos Allende), the Philadelphia Experiment of 1943, and the very real possibility of inter-dimensional space travel—"the roads to other worlds may be closer than we previously imagined!" Allen, or should I say "Allende", contacts renowned selenographer Dr. Jessup, who reports (with utmost discretion!) to friend and colleague Dr. Valentine, who whispers to Dr. Berlitz, who dutifully relays to his readers that all is not what it seems in the US government. It's 1943 and the military, with Einstein in cahoots, is warping and re-refracting magnetic fields, trying to make things disappear. They are only too successful: USS Eldridge vanishes, and on board, protons and electrons swirling, men are evaporating left and right, falling through to another dimension. When they're dragged back to earth, they've all got PTSD and are sworn to silence. Berlitz doesn't have too much to say about this (though he will in his subsequent book The Philadelphia Project—Project Invisibility) except that, well, whatever made that destroyer disappear is probably what's letting those aliens stir up so much trouble in the Bermuda Triangle, as they plant the first flags and pitch the first tents of empire on this vast, but heavily populated, planet.

And it is in these final moments of reflection that Berlitz, whose writing has been miraculously devoid of paranoia or fear, takes a darker tone:

Remembering Columbus, standing on the brink of the discovery of the New World, one may observe, however we feel about the justice of the European incursion, that it subsequently proved unquestionably better for survival purposes, to have been a questing and curious European rather than a nonquesting Amerindian, the greater number of which were destined for extinction. It is likely that intelligent entities are questing in outer and inner space. It will be better for us to continue to explore and search on our own, preferably as a united planet, rather than passively to await discovery and settlement of our world by other travelers on the road to and from the stars.

+++

A linguist by trade, Charles Berlitz was, to say the least, a prolific man: he spoke 32 languages and wrote 19 books on "anomalous phenomena," a subject matter for which he clearly had a passion. (He only published one book on linguistics.)

Chloé Wilcox writes, makes art, and lives in New York City. She has a special interest in medieval art history, mystic nuns, and ceramics.

View Without a Trace in the catalog here.